Home » Emergency contraception

This article completes the 2025 IPU Review series on contraception. Previous articles can be found at ipu.ie/ipu-review > Archive Articles.

Emergency contraception is indicated to reduce the risk of a pregnancy occurring following unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) or failure of contraception. There are three types of emergency contraception:

The two oral emergency contraceptives, ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel, can be accessed in most community pharmacy settings, following a consultation with the pharmacist. As clinical guidelines are regularly updated, this article summarises the considerations a pharmacist can have when choosing the most appropriate action for a woman seeking emergency contraception.

Emergency contraception is indicated after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI). There is a possibility of pregnancy following UPSI anytime from day 21 after childbirth (unless the woman is fully breastfeeding and amenorrhoeic, in which case pregnancy is not possible for six months after childbirth). Pregnancy is also possible from five days after a miscarriage, abortion or ectopic pregnancy. Emergency contraception may also be required if regular contraception has become compromised, but it is important to obtain a full history regarding the contraception use and the reason for the woman presenting for emergency contraception prior to providing advice on the most appropriate form of emergency contraception.

The copper-IUD is the most effective form of emergency contraception, with a reported effectiveness rate of >99.9 per cent. While the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for each of the oral emergency contraceptives state that they can be taken ‘at any time during the menstrual cycle’, the copper-IUD is the only form of emergency contraception effective after ovulation. Should there be a possibility that the woman has ovulated prior to presenting to the pharmacy, this must be explained to the woman. While a copper-IUD cannot be inserted by a pharmacist, all women should be informed that the copper-IUD is the most effective method of emergency contraception.

Guidelines on this have been issued by the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health (FSRH), now known as the College of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (CoSRH), who are a UK-based professional organisation that provides standards and guidance in sexual and reproductive health and is a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) accredited group. The guidelines state that if a woman is referred on for a copper-IUD, oral emergency contraception should be given at the time of referral in case the Cu-IUD cannot be inserted, or the woman changes her mind.

The two oral emergency contraceptives work by the same mechanism — delaying ovulation. This means two main things: (i) ovulation is still likely to occur in the cycle after emergency contraception has been taken, just at a later date; and (ii) oral emergency contraception does not work after ovulation has occurred. A pharmacist will need to establish that a woman is likely to be in the part of her cycle before ovulation has occurred, by asking questions such as ‘when was your last period?’, ‘is your cycle regular?’ and ‘if your cycle is regular, how many days apart are your periods approximately?’. Once it has been established that the woman is likely to be in the part of her menstrual cycle prior to ovulation, some other questions can help establish whether levonorgestrel or ulipristal acetate will be more suitable.

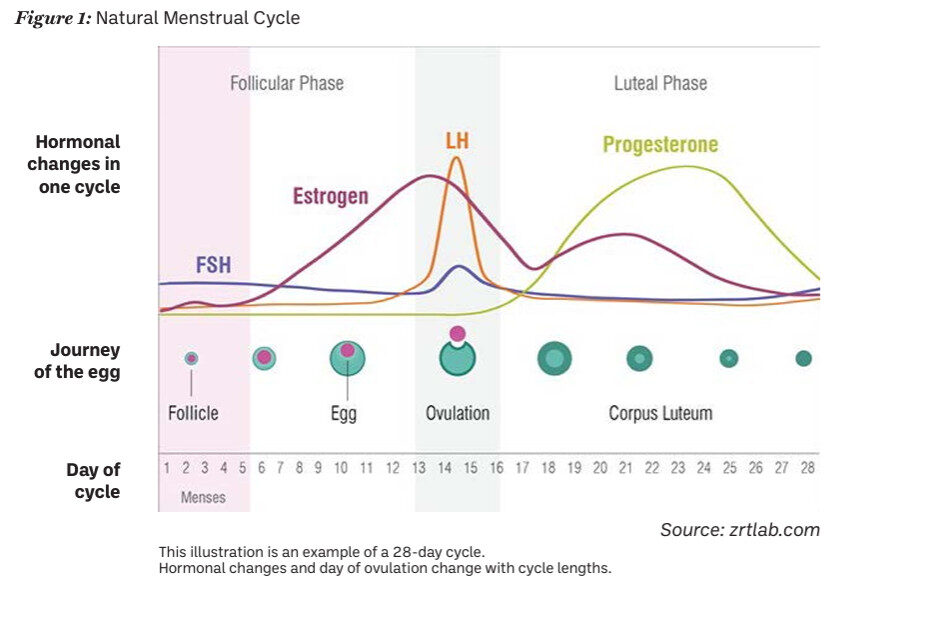

It is imperative that pharmacists providing emergency contraception have an understanding of the hormones and key timings of the menstrual cycle (Figure 1). Luteinising hormone (LH) provides the trigger for ovulation, and both levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate work by suppressing the luteinising hormone peak, which delays ovulation by approximately five days. In a natural menstrual cycle (no hormonal contraceptives), a pregnancy is most likely to happen if UPSI occurs in the five days before ovulation or on the day of ovulation — this is considered to be the highly fertile time of a woman’s cycle. The reason for this is that sperm are viable in the female genital tract for about five days, whereas the egg is viable for less than one day.

Fig. 1: Natural Menstrual Cycle

Source: zrtlab.com

Levonorgestrel is a progestogen, which acts by suppressing the LH peak. This delays, or in rare instances blocks, ovulation for five days. Levonorgestrel is less effective than ulipristal acetate in the highly fertile period, as levonorgestrel must be taken prior to the start of the LH surge. Levonorgestrel can be used if UPSI occurred within the last 72 hours and is the preferred choice in a few different situations:

Levonorgestrel is not recommended for patients who are at risk of ectopic pregnancy (previous history of salpingitis or of ectopic pregnancy), with pre-existing thromboembolic risk factor(s), especially personal or family history suggesting thrombophilia or who have severe hepatic dysfunction. Also, severe malabsorption syndromes, such as Crohn’s disease, might impair the efficacy of levonorgestrel.

Ulipristal acetate is a progesterone receptor modulator which acts by suppressing the LH peak. Similar to levonorgestrel, this delays ovulation by at least five days. Ulipristal acetate is approximately 98.5 per cent effective up to 120 hours post UPSI and is considered to be more effective than levonorgestrel. It has one major drawback — it interacts with other progesterone/progestogen containing products. This means that if a woman seeking emergency contraception has taken medicine containing progesterone or progestogen (including contraception, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and others), in the seven days prior, or will be taking such medicines in the five days after emergency contraception, the effectiveness of ulipristal acetate can be compromised. This means that for any patient who requires emergency contraception and who is on hormonal contraception, they will need to delay restarting their hormonal contraception/HRT for five days after taking ulipristal acetate. Additional precautions, such as the use of a condom, will be required by all patients after taking oral emergency contraception. The time to contraceptive cover being re-established from hormonal contraception is as per the SmPC for each individual hormonal contraceptive (generally two days for progestogen-only pill, seven days for combined hormonal contraception, and nine days for Qlaira).

Due to its superior effectiveness, ulipristal acetate is the preferred choice of oral emergency contraception in the following circumstances:

Design noteThere is conflicting advice regarding the effectiveness of oral emergency contraception in those who are over 70kg or those who have a BMI of >26kg/m2. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and subsequently the PSI have both stated that the evidence about reduced effectiveness of oral emergency contraception in individuals who weigh >70kg or have a body mass index (BMI) of >26kg/m2 is not conclusive. The PSI emphasise the importance of providing emergency contraception as soon as possible after UPSI. The FSRH suggest using ulipristal first line and a double-dose of levonorgestrel second line. A double dose of levonorgestrel due to weight considerations is outside of the product SmPC. Thus, on balance, in Ireland, the guidance is to provide emergency contraception as soon as possible. Patients who are overweight should first be signposted for a copper-IUD placement, as weight has no effect on the efficacy of a copper-IUD. The preferred oral emergency contraceptive, if suitable, is ulipristal acetate. If ulipristal acetate is not suitable, levonorgestrel 1.5mg could be offered.

There are three specific circumstances in which ulipristal acetate is unsuitable due to drug-drug interactions:

With either form of oral emergency contraception, serious side-effects are rare. The side-effects commonly experienced include headache, nausea and dysmenorrhoea. If a patient is so nauseous that they vomit within three hours of taking oral emergency contraception, a further dose of the same oral emergency contraceptive as was given originally, should be dispensed. As both oral emergency contraceptives work by delaying ovulation, both have the side-effect of delaying menstruation. Every patient should be advised to take a pregnancy test if their period is delayed by more than seven days. However, it is useful to know that 20 per cent of patients who took ulipristal acetate have a delay of more than seven days to their period, as do 10 per cent of patients who took levonorgestrel. Many oral emergency contraception tablets contain lactose and should not be supplied to patients with the rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, the Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption. Hypersensitivity to an active substance or excipients should be considered.

Finally, as oral emergency contraceptives delay ovulation, there is the possibility that women may require emergency contraception twice in one cycle. The general recommendation is that if levonorgestrel is provided the first time it is required in a cycle, levonorgestrel should be provided again after the second instance of UPSI and similarly for ulipristal acetate. It is also important to remember that oral emergency contraceptives are not harmful to a very early pregnancy.

Pharmacists will need to structure any consultation with a woman requesting oral emergency contraception to ensure that they gather all the relevant information to consider all the factors mentioned above: time since UPSI, use of other hormone-containing medicines, possible drug-drug interactions and other factors affecting choice of emergency contraception. It should be explained to all women that oral emergency contraception is intended for occasional emergency use and should not be considered a substitute for effective regular contraception. Information should also be provided on the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases.

As outlined at the start of this article, all women should be informed that the copper-IUD is the most effective method of EC. Pharmacistsof all points within this article the pharmacist is not satisfied that the supply of the product to the patient is appropriate, the pharmacist should refer the woman to another healthcare professional or service more appropriate to meet the woman’s needs.

Further information and resources can be found at: