Home » CPD Managing Shingles

Shingles is most commonly characterised as a painful, blistering rash on the trunk. It is caused by reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus (VZV).

VZV is a herpes virus associated with two major clinical syndromes: chickenpox (also known as varicella), and shingles (also known as herpes zoster or zoster). Primary infection with VZV causes chickenpox. Following the primary infection, the virus can remain latent in dorsal root ganglia, cell bodies of sensory neurons. Reactivation of the latent virus results in shingles, as the virus travels down a sensory nerve to form a blistering rash on the skin supplied by that nerve.

The lifetime risk of primary infection with VZV, and resulting chickenpox, in a country with a temperate climate and absence of a national VZV vaccination programme, such as Ireland, is over 95 per cent. In contrast, the lifetime risk of shingles is approximately 25 – 35 per cent. Reactivation of latent VZV, resulting in shingles, can occur at any age, although its incidence increases with age. This is thought to be due to an age-related decline in immunity, known as immunosenescense. Immunosuppression, whether age-related or relating to a disease or treatment, increases the risk of shingles. However, the majority of cases occur in immunocompetent patients. The manner in which shingles occurs, via reactivation of VZV, means it has no seasonal pattern.

Shingles is not a notifiable disease. Therefore, there is limited data on the incidence of shingles in Ireland. An Irish cross-sectional observational study in GPs reported between one and three cases of shingles presenting per month, with 80per cent of presentations occurring in those ≥50 years. The incidence rate in those ≥50 years in Europe lies between 5.2 and 10.9 per 1,000 person-years.

Shingles is only infectious to those who have not previously been infected with VZV, i.e. those who have never had chickenpox. It is primarily transmitted to these individuals by direct contact with fluid from the blistering rash. It can be transmitted via indirect contact however, including via inhalation of virus shedding from open lesions. There in a higher risk of spread via indirect contact when an immunocompromised person is suffering from the illness and has severe disease.

Persons who have had chickenpox are not at risk of transmission from an individual suffering with shingles. If anything for these persons, exposure to an infected individual may boost immunity and help prevent shingles.

Shingles has a high burden of disease due to the signs, symptoms and secondary complications.

The classic presentation of shingles is a painful, blistering rash on the trunk. The key feature of the rash is its dermatomal distribution, as it presents on the skin supplied by the affected nerve, usually on the torso. Pain typically occurs in the affected area approximately two to three days before the rash develops. It is often characterised as a burning pain, which may be constant or intermittent. The rash itself presents with redness of the skin and a collection of small fluid-filled blisters, termed vesicles. Vesicles continue to form for three to five days and then progressively dry and crust. Patients are considered infectious to susceptible individuals from the appearance of vesicles until all lesions have crusted. This is generally five days in duration. The rash typically heals within two to four weeks, but commonly leaves scarring and permanent pigmentation in the area. Up to 20 per cent of people may experience systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, headache and malaise. Shingles is usually diagnosed clinically due to the classic presentation of the illness.

Other manifestations of shingles include ophthalmic shingles (herpes zoster ophthalmicus) and Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster oticus). Ophthalmic shingles occurs when latent VZV is reactivated in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. This will result in pain and the characteristic vesicular rash located ipsilaterally on the forehead. Ramsay Hunt syndrome occurs with reactivation in the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve, although other cranial nerves may also be involved. It typically presents with a triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, ear pain and vesicles around the ear and auditory canal.

Pharmacists who suspect a presentation of shingles should promptly refer all patients for medical review as the use of antivirals has shown to improve outcomes. Patients who are immunocompromised should be referred to secondary care, while those who have eye involvement should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist.

The most common complication of shingles is post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). PHN is a chronic pain that persists long after the resolution of other symptoms of shingles such as the rash. Exact definitions of PHN differ, but a commonly accepted definition is pain persisting for at least 90 days after the onset of the rash. The duration of pain with PHN significantly varies. It usually resolves within six months but has been reported to last for years. It may be constant or recurrent and can have different levels of severity. The risk of developing PHN has been reported to range from 5 per cent to 32 per cent, depending on its exact definition.

Other complications of shingles include secondary bacterial skin infections and ocular complications associated with ophthalmic shingles, such as conjunctivitis, keratitis, ulceration of the cornea and glaucoma.

An Irish cross-sectional observational study in GPs reported between one and three cases of shingles presenting per month, with 80per cent of presentations occurring in those ≥50 years.

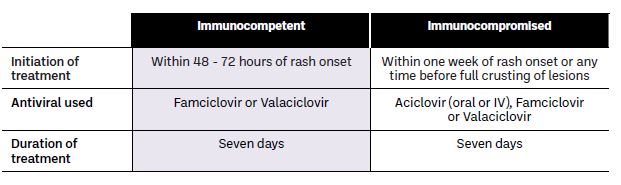

Shingles is usually a self-limiting illness. Antivirals may be used for treatment as they reduce the viral load, shorten the duration of viral shedding, manage pain and reduce the risk of complications such as PHN. The use of antivirals differs in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients (see Table 1).

Table 1: Treatment algorithm for shingles

Table 1: Treatment algorithm for shingles

An important benefit of the use of antivirals is that their administration in shingles patients has been shown to decrease the risk of PHN. PHN is notoriously difficult to treat. Medication options include analgesia, anti-depressants and anticonvulsants, with the latter options being used when analgesia is ineffective. Options for analgesia include paracetamol, NSAIDs, and weak or strong opiates. Anti-depressants which may be used include amitriptyline and duloxetine, while the anticonvulsants options are pregabalin and gabapentin. Topical treatment options available consist of lidocaine patches and capsaicin cream. High-strength capsaicin patches may be trialled in refractory cases in a hospital setting.

Vaccination against shingles aims to reduce the incidence, severity and complications of the disease. But why vaccinate against an infection you already have? Shingle vaccines differ from other vaccines as they are primarily administered to those who have already been infected with VZV. Therefore, these vaccines function as ‘therapeutic vaccines’. The aim of the vaccination here is to invoke an immune response in order to prevent reactivation of latent virus, which would result in shingles.

Two types of shingles vaccines are currently available on the Irish market: Shingrix (GSK) and Zostavax (Merck Sharp & Dohme). Zostavax is a single-dose live attenuated vaccine, while Shingrix is a recombinant zoster vaccine. Only Shingrix will be discussed in this article as Merck Sharp & Dohme confirmed to the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) in August 2023 that they will be voluntarily discontinuing the manufacture and supply of Zostavax. Details of Shingrix are outlined in Table 2.

Clinical trials of a two-dose schedule of Shingrix, with median follow-up of four years, demonstrated efficacy of 100 per cent in those at 50 – 69 years, 93 per cent in those at 70 – 79 years, and 71 per cent in those ≥80 years. Efficacy has been shown to differ between immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients, with efficacy being slightly lower in immunocompromised.

Table 2: Details of the GSK Shingrix vaccine

Vaccination against shingles is not currently included in the national immunisation programme in Ireland, a programme based on advice and guidance from the National Immunisation Advisory Committee (NIAC). Therefore, as of January 2024, if patients are considered eligible for vaccination (≥50 years or ≥18 years if increased risk of shingles) they can privately source the shingles vaccine from a GP or pharmacy.

The Medicinal Products (Prescription and Control of Supply) Regulations 2003 (as amended by S.I. No 449 of 2015, S.I. No 401 of 2020 and S.I. No 32 of 2022), enables pharmacists to supply and administer Zostavax powder and solvent for suspension for injection herpes zoster vaccine (live, attenuated). The eight schedule of this legislation was amended (S.I. 32 of 2022) to include Shingrix powder and suspension for injection herpes zoster vaccine (recombinant, adjuvanted). Both vaccines are prescription-only-medicines, legally classified as schedule 1A. Therefore, if being dispensed but not administered, the vaccine must be supplied on foot of a prescription.

In order for pharmacists to administer the shingles vaccine in Ireland, they must complete the ‘Administration of Herpes Zoster Vaccination’, a free, self-directed and fully online programme available via the IIOP. This course must be done in conjunction with all other vaccination training requirements, details of which can be found on the PSI and IIOP websites. Administration of this vaccine must also be done in accordance with the current immunisation guidelines for Ireland.

Will vaccination against shingles be included in the national immunisation programme? This remains to be seen. The Department of Health (DoH), following a recommendation from NIAC, has requested that HIQA undertake a health technology assessment (HTA) to review evidence for the addition of a shingles vaccine to the adult immunisation schedule in Ireland. The protocol for this HTA was published in December 2023. The HTA will assess parameters such as the clinical effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness and budget impact, as they relate to the addition of the shingles vaccine to the immunisation schedule. The ethical, legal, social and organisational implications of such an addition will also be considered. There is no specified timeline for this process.

A similar process has already been undertaken for expansion of the childhood immunisation schedule to include vaccination against chickenpox. This HTA was published in July 2023 and advised that chickenpox vaccination is safe and effective, and that a one-dose vaccination strategy is cost-effective compared to no vaccination. A two-dose schedule was also reported to be cost-effective compared to no vaccination, but less so than a one-dose schedule. Following the HTA, the DoH has requested the HSE outline a plan and costs associated with implementation of chickenpox vaccination. If the plan and costs are considered acceptable to the DoH, it is likely that chickenpox vaccination will be added to the Irish childhood immunisation schedule.

Something to consider is a predicted rise in the incidence of shingles for the first 40 – 60 years if chickenpox vaccination is to be introduced, even with a concomitant shingles vaccination programme for older adults. The introduction of such vaccines would result in a large decrease in cases of chickenpox, provided vaccine uptake is high (>70 – 80 per cent). It is thought that immunity of adults (who have previously had chickenpox) against shingles is boosted when they are exposed to children infected with chickenpox. Therefore, with widespread chickenpox vaccination, this exposure and natural boosting in adults would be reduced, resulting in decreased immunity to shingles, and increased shingles incidence. Vaccination against shingles is not considered a solution to this problem as it would be predominantly middle-aged adults affected, who would not be eligible for shingles vaccination.

Ultimately, the decision as to whether shingles vaccination will be added to the adult immunisation schedule lies with the DoH. The first step has been taken with the request for a HTA from HIQA, but only time will tell.

Can the shingles vaccine be given to patients not previously infected with chickenpox?

A prior history of chickenpox is not required prior to vaccination with either vaccine. Therefore, there is no requirement for testing to establish a past history of infection with VZV.

Can the shingles vaccine be given to those who have already had shingles?

Yes, either vaccine can be administered to patients with a history of shingles. Although the majority of people only experience a single episode of shingles, recurrence is possible. The risk of shingles recurrence in immunocompetent persons is thought to lie between 1 per cent and 6 per cent.

When can the shingles vaccine be administered to those with a recent history of shingles?

The shingles vaccine can be administered following natural infection provided the vaccine is not contraindicated, and the patient has recovered from acute infection with no active lesions. There is no specified recommendation on the duration of time required between recovery and administration of the vaccine. The benefit of vaccination immediately after recovery is unclear, as patients will have naturally boosted their immunity. Sources outline that it is preferable to defer vaccination for 12 months after resolution of shingles to ensure a more effective immune response.

Can the shingles vaccine help those with PHN?

Neither Zostavax or Shingrix are licensed or recommended for PHN. The vaccine can be administered in those with PHN if there are no contraindications or concomitant symptoms.

You can find more information on shingles and chickenpox in the Immunisation Guidelines for Ireland; Chapter 23: Varicella Zoster, available at rcpi.ie > Healthcare Leadership > NIAC > Immunisation Guidelines for Ireland). Information on requirements for administration of the shingles vaccine is available on the PSI website at psi.ie > Education > Vaccinations training.

References available on request.

Meabh Ryan

MPSI

Highlighted Articles