Home » Addressing high anticholinergic and/or sedative drug burdens

This CPD article from Clare Kinahan, Chief II Pharmacist at Midlands Regional Hospital Tullamore, outlines the risk associated with the use of sedative and anticholinergic medications, the tools available to assess the level of risk and how shared decision making can be employed to reduce it.

Medication Review is defined as “a structured, critical examination of a person’s medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the person about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication related problems and reducing waste”. Pharmacist-led medication review has been shown to reduce the prescribing of sedative and anticholinergic medications in older people and there are tools that can be used to assist in this process.

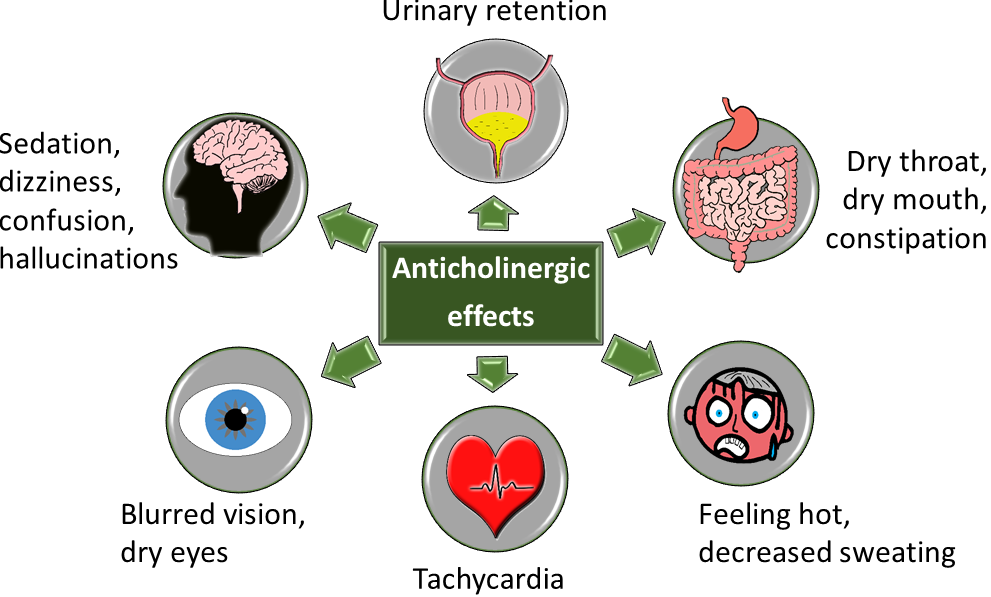

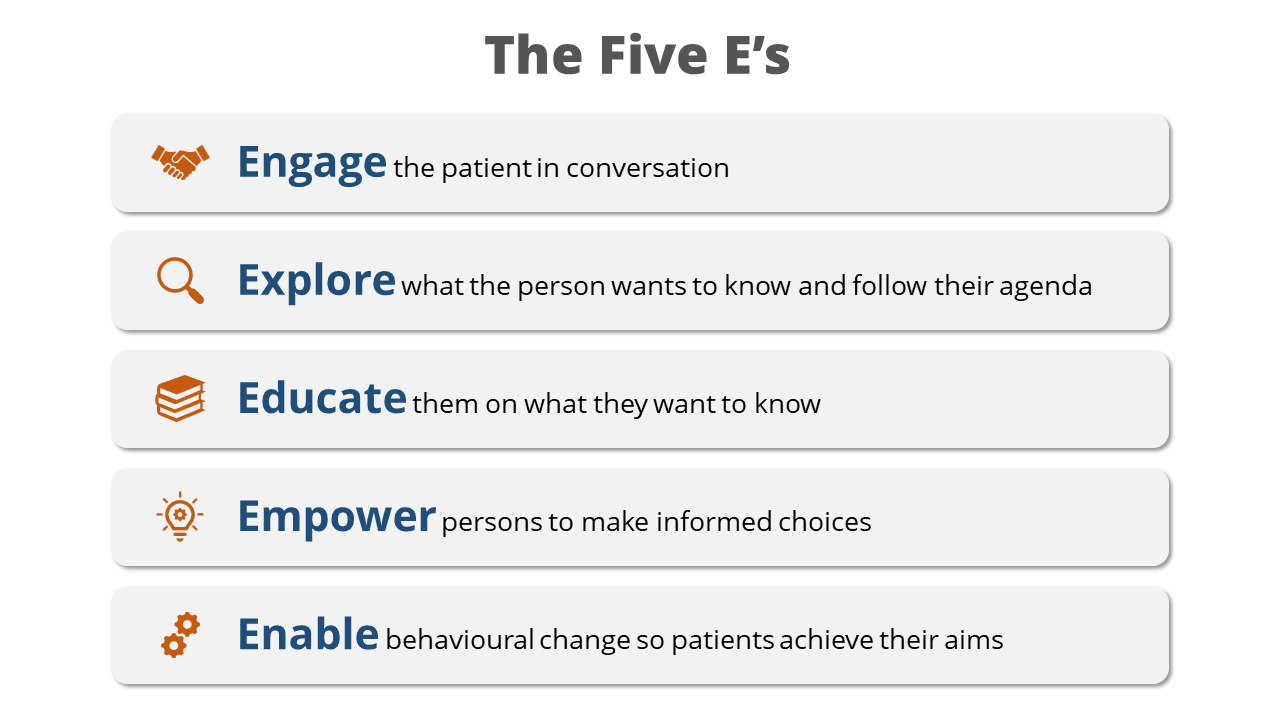

The Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria can be used to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP). Many of these criteria relate to the use of sedative and anticholinergic medications because the physiological impact of ageing on drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics makes older people more susceptible their adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The cumulative burden of these medications contributes to the associated risk. Medications with clinically significant sedative and/or anticholinergic effects can cause central nervous system ADRs including drowsiness, dizziness, psychomotor/balance impairment, confusion and delirium, and they have been linked with an increased risk of falls, functional impairment and cognitive decline in older adults. Anticholinergic medications additionally cause a range of peripheral adverse effects including urinary retention, dry mouth, constipation, tachycardia and blurred vision. Strongly anticholinergic medications include urinary antispasmodics, for example, oxybutynin; TriCyclic Antidepressants (TCAs), for example, amitriptyline; antipsychotics, for example, chlorpromazine; and sedating antihistamines, for example, promethazine. These are additionally cautioned in patients with a history of urinary retention, cardiac conduction abnormalities, chronic constipation and narrow angle glaucoma.

Anti-Cholinergic Burden Scales can be used to assess the overall anticholinergic burden of a patient’s drug regimen. The greater the score, the greater the risks. Online resources and tools can be used to calculate the score and to identify potential alternative therapies with lower anticholinergic burden. There are over twenty different published anticholinergic burden scales. The AEC scale, a central anticholinergic burden scale (available at medichec.com) considers blood brain barrier penetration. The ACB online calculator (available at acbcalc.com) combines the scores of two scales (the German Anticholinergic Burden score and the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale), but still omits some medications which are scored on other scales, for example, prochlorperazine. The CRIDECO Anticholinergic Load Scale (CALS), the most recently published scale, includes more medications than its predecessors.

Image 1: Anticholinergic effects

Source: Medicine Safety Portal at Wessex Academic Health Science Network, available at medicinesafety.co.uk. Design note: Image available at https://www.medicinesafety.co.uk/2019/02/anticholinergics-safety-concerns.html

The Drug Burden Index (DBI) is a measure of the cumulative exposure to anticholinergic and other sedative drugs, including benzodiazepines, hypnotics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, gabapentinoids, opioids, dopaminergics and antiemetics. A high DBI (see gmedss.com), is associated with poor clinical outcomes in older patients, including functional impairment (for example walking speed, balance and falls), frailty, higher hospitalisation and mortality rates due to associated impairment of physical and cognitive function. Unlike the ACB, the DBI is calculated based on the prescribed dose of the drug, and so can be reduced by dose reductions.

Despite their potential to cause harm, many anticholinergic/sedative medications are prescribed for clinical conditions necessitating ongoing use. Tools such as STOPP/START, Anti-Cholinergic Burden Scales and the DBI are screening tools only. ‘Potentially’ inappropriate medicines may still be deemed appropriate, if the benefits outweigh the risks for the individual. Further clinical information and the patient’s experience of treatments need to be considered.

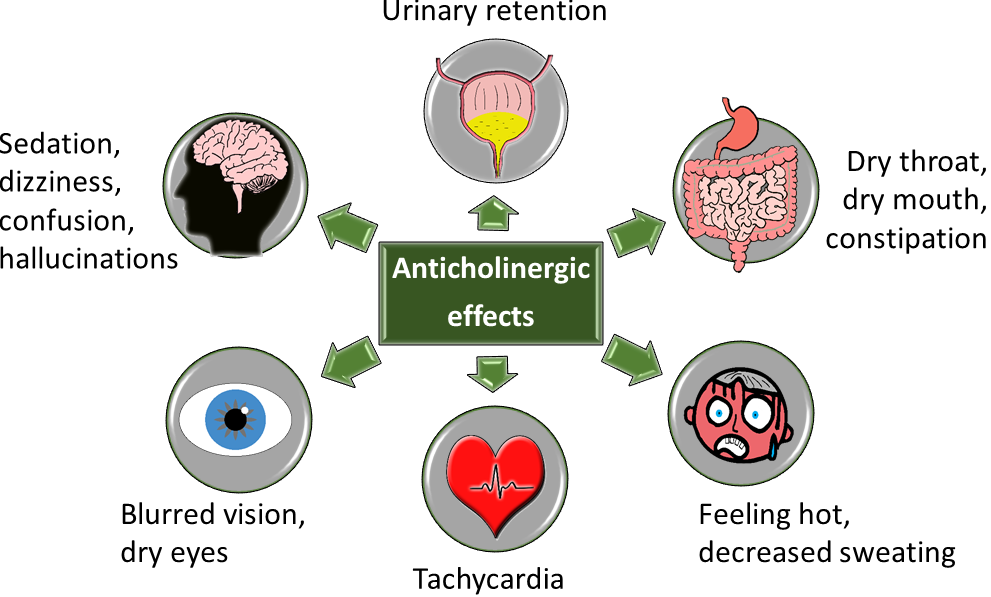

Deprescribing through Shared Decision Making (SDM) can improve prescribing appropriateness. SDM is a joint process in which a healthcare professional works together with a person to reach a decision about care. Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping a medication, and it should be considered if a shared decision is reached that a medication is likely to cause the individual more harm than benefit. Professionals should only make deprescribing recommendations if they have sufficient knowledge, experience and information available to them on the benefits and harms of the particular medicine for the particular individual. It can be difficult to know if a medication is still delivering benefits or if the condition it was treating has resolved. Dose reductions or tapering can facilitate identification of the lowest effective dose as well as decreasing the likelihood of Adverse Drug Withdrawal Reactions (ADWRs) that can occur on sudden cessation. ADWRs are adverse physiological changes occurring when a medication is withdrawn rapidly, which exceed the symptoms that medication was being used to treat. Where dose reduction is not feasible, a trial of holding a medication with monitoring for the return of symptoms can be helpful. Simultaneous deprescribing of medications with potential ADWRs should be avoided, to enable appropriate monitoring and to encourage patient engagement. Deprescribing resources are available to guide shared decision making and withdrawal, for example choiceandmedication.org/ireland, medstopper.com and deprescribing.org. Using a model, such as the five E’s (see Image 2) can help to engage patients in medicines-related decisions.

Image 2: The Five E’s

Image developed with permission of N.Barrett and reproduced with permission of IIOP.

Urinary antispasmodics should be reviewed if they have had minimal or no benefit in treating bladder spasms or urinary incontinence. Many medications can cause urinary incontinence, including diuretics and the cholinesterase inhibitors, for example, donepezil, and prescribing cascades (when a medication is prescribed to manage side effects of another medication) should be avoided if possible. Urinary antispasmodics can be stopped abruptly if causing significant ADRs or withdrawn gradually with monitoring for the recurrence of symptoms.

Antiemetics have many and diverse potential ADRs, and so the dose and duration of use should be the minimum required to control symptoms. Domperidone and ondansetron do not usually penetrate the CNS in the same way as cyclizine, hyoscine, prochlorperazine and metoclopramide, but they do have potential to cause QT prolongation.

First-generation antihistamines lead to deleterious changes in sleep patterns and increased daytime sleepiness and should not be prescribed as hypnotics. Avoidance of sedating antihistamines for any indication in over 65-year-olds is recommended as second- and third-generation agents are safer/more appropriate. If prescribed for seasonal allergies, topical agents are preferred or if necessary oral antihistamines should only be prescribed seasonally. They can be stopped abruptly if causing significant ADRs or withdrawn gradually with monitoring for the recurrence of symptoms.

The benefits dopamine agonists offer in the management of Parkinson’s disease will likely outweigh associated anticholinergic/sedative risks. However use of the dopamine agonists’ ropinirole and pramipexole for the management of restless legs syndrome (RLS) should be reviewed if ADRs are outweighing their perceived benefits. Low iron is often the cause of RLS and so iron studies should be performed before initiating medication for RLS. Mild and/or intermittent RLS symptoms, can be treated by non-pharmacological means, such as heat, massage, exercise and avoidance of caffeine and aggravating drugs. Dopamine agonists ADRs include impulse control disorders and worsening of RLS symptoms. If use has been long-term, withdrawal should be gradual to avoid ADWRs including return of symptoms, anxiety, nausea and sweating.

The benefit antipsychotics offer in the management of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, psychotic depression or bipolar affective disorder will likely outweigh associated anticholinergic/sedative risks. However, they should not be used solely to treat insomnia and use for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), is only appropriate if aggression, agitation or psychosis is causing distress or risk of harm, to the patient or others. Long term antipsychotic use for the management of BPSD should be reviewed and stopped if ineffective or within three months of symptoms resolving. Antipsychotic ADRs include exacerbation of movement disorders, weight gain, diabetes, QT interval prolongation, and an increased risk of stroke, arrhythmias, syncope and falls. If use has been long term withdrawal should be gradual to avoid ADWRs including dyskinesia, insomnia, nausea, restlessness.

“Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping a medication, and it should be considered if a shared decision is reached that a medication is likely to cause the individual more harm than benefit.”

Antidepressants should be reviewed if the patient has recovered from a depressive episode and is at low risk of recurrence. Specialist input may be required to determine if this is the case, and to guide the gradual withdrawal if use has been long-term. Some antidepressants, for example, amitriptyline, are prescribed to treat neuropathic pain. Amitriptyline is strongly anticholinergic and should be reviewed if it has had minimal or no benefit. ADWRs can include anxiety, chills, gastrointestinal distress, headache, insomnia, irritability, malaise and myalgia.

Antiepileptics/gabapentinoids benefits when used for seizure control will likely outweigh associated anticholinergic/sedative risks. However, they are also prescribed for other indications, for example, pregabalin for anxiety, and carbamazepine and gabapentinoids (pregabalin, gabapentin) in the management of restless legs syndrome (RLS) or neuropathic pain. Use for such indications should be reviewed if ADRs are outweighing their perceived benefits. Shared treatment goals should ideally be agreed and documented prior to initiation. A successful trial of medications for neuropathic pain would result in a ≥50 per cent reduction in pain intensity. Antiepileptics have diverse ADRs and interactions. Gabapentinoids have dependence potential and are cautioned in substance use disorders (SUD), depression, gait instability, respiratory failure and obesity. If use has been long-term, withdrawal should be gradual to avoid ADWRs.

Opioid use should be reviewed if ADRs are outweighing their perceived benefits in the long–term management of non-cancer pain. There is a lack of evidence of efficacy for long term opioids in the management of osteoarthritis. There is a lack of evidence of efficacy for long-term use of doses over 50mg morphine equivalent dose (MED) per day and the risk of harm substantially increases at over 120mg MED/day with no increase in benefit. Calculators and opioid conversion charts (for example see olh.ie > Health and Social Care Professionals > Palliative Meds Info > Key documents), are available to calculate MED.

Long-term use is associated with dependency, tolerance to analgesic effects and increased fracture risk both by decreasing bone mineral density and increasing the risk of falls. Other ADRs associated with long-term use include immunosuppression, increased cardiovascular risk, respiratory depression and sexual dysfunction. Tools are available to form the basis to assist planned reduction/cessation with the patient to monitor and rate ADWRs during the withdrawal process. Potential ADWRs include abdominal cramping, diarrhoea, anxiety, chills, sweating, insomnia, restlessness. It is reasonable to continue opioids in limited life expectancy to avoid ADWRs.

Long-term benzodiazepine use may be appropriate for multiple sclerosis, intractable epilepsy or palliative care, but benzodiazepine and Z-Drugs (BZRA) are not recommended for >four weeks for anxiety/insomnia. Withdrawal should be considered in those experiencing ADRs including falls, daytime sedation or cognitive impairment but it needs to be gradual and tailored to the individual. SDM has been employed to achieve successful withdrawal. Patients with unmanaged depression or another aggravating condition may need referral to psychiatric services for safe withdrawal.

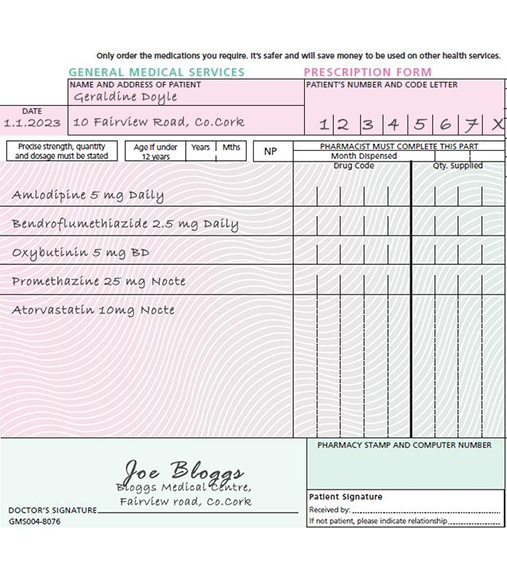

Key message: Patients/carers should be engaged in shared decision making (SDM) to determine if their experience or perceptions of the potential benefits of anticholinergic and sedative medications outweigh their experience of/or concerns about potential adverse drug reactions. Exercise: Geraldine Doyle an 82-year-old with a history of falls. She tells you that she feels quite sleepy during the day and asks if any of her medications could be causing this. Consider which medications might be reviewed and what if any alternatives you might suggest. Answer:

Oxybutynin: is a strong anticholinergic urinary antispasmodic. If ongoing management of overactive bladder is important to the patient, mirabegron could be trialled as an alternative with monitoring for efficacy and potential ADRs (for example, increased heart rate, urinary tract infections). Promethazine: is a strongly anticholinergic sedating antihistamine, and it’s use as a hypnotic should be avoided if possible. If prescribed for generalised itch/rash/allergy a second generation antihistamines would be preferable. If prescribed for local symptoms, a locally acting agent would be preferable.

Answer:

Oxybutynin: is a strong anticholinergic urinary antispasmodic. If ongoing management of overactive bladder is important to the patient, mirabegron could be trialled as an alternative with monitoring for efficacy and potential ADRs (for example, increased heart rate, urinary tract infections). Promethazine: is a strongly anticholinergic sedating antihistamine, and it’s use as a hypnotic should be avoided if possible. If prescribed for generalised itch/rash/allergy a second generation antihistamines would be preferable. If prescribed for local symptoms, a locally acting agent would be preferable. Clare Kinahan

Chief II Pharmacist,

Midlands Regional Hospital Tullamore

Highlighted Articles