The information provided was valid at the time of the publication of this CPD article.

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined as any involuntary leakage of urine. UI can have a significant impact on the physical, psychological and social wellbeing of a person. In general, UI is approximately twice as common in women as in men, and is more common in older than younger persons. Contributory factors include pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, ageing, neurological damage, stroke, birth defects and multiple sclerosis. The highest prevalence and symptom severity of urinary incontinence affect women over 70 years, with more than half of those diagnosed with severe incontinence reporting detrimental effects on their employability, social function and willingness to leave the house.

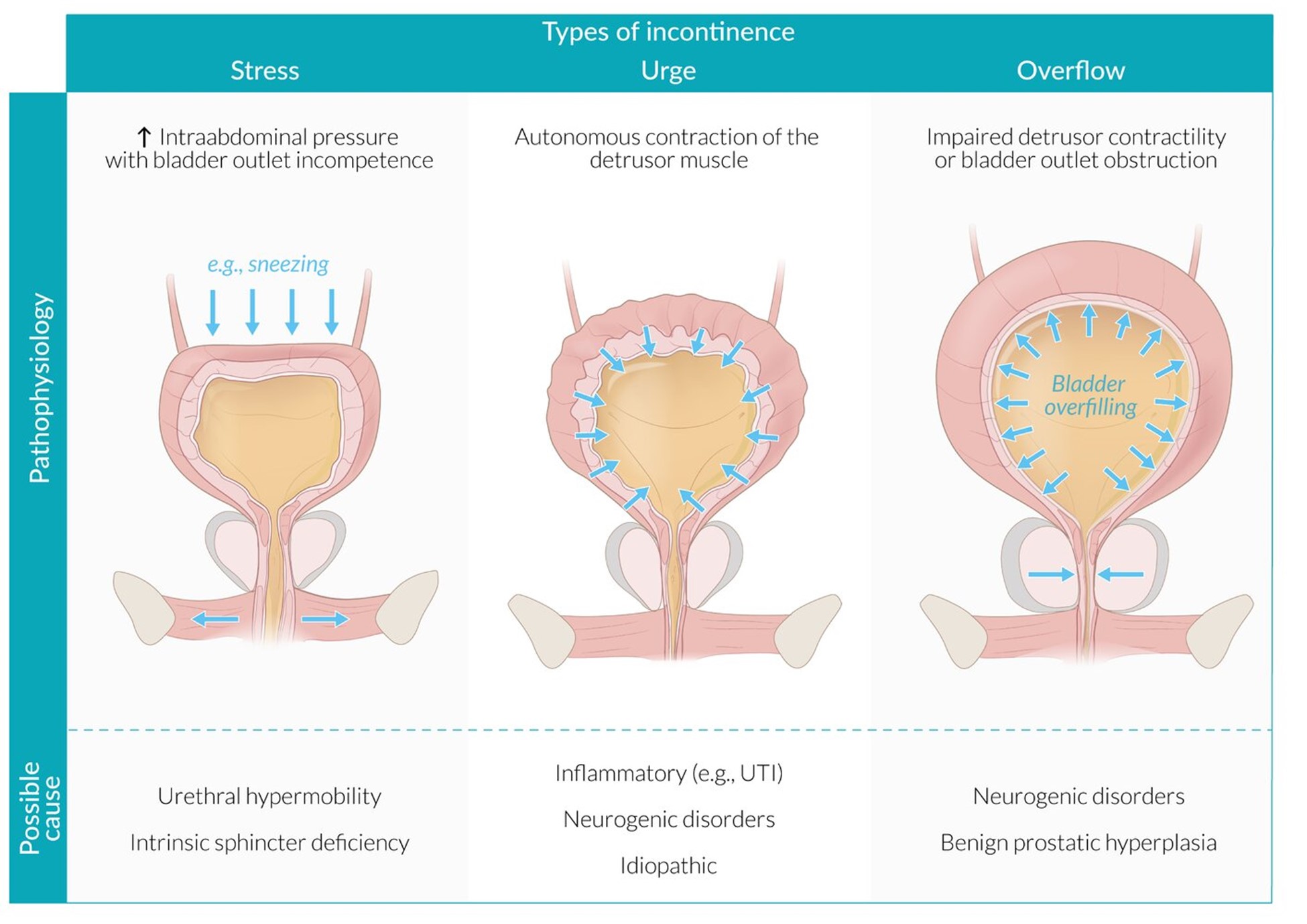

The three main subtypes of UI are:

Other types of incontinence:

Urinary frequency is generally considered as ≥ 8 micturitions during waking hours, though this number is variable depending on hours of sleep, fluid intake and co-morbidities.

Overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) is defined as urgency, usually with increased frequency and nocturia, which may occur with or without urgency incontinence. Stress urinary incontinence and overactive bladder syndrome are the cause for over 90% of cases of urinary incontinence.

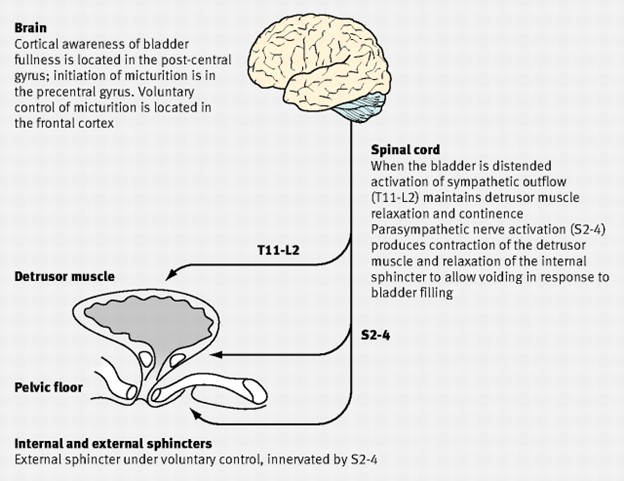

Figure 1: Physiology of urinary continence

Urinary continence in females depends on urine being stored in a receptive bladder closed by a competent sphincter mechanism. When the bladder is full, nerve impulses pass to the pontine micturition centre in the brain which triggers urination. The detrusor muscle contracts as a result of acetylcholine acting on muscarinic receptors. Incontinence can occur when there is detrusor instability or a failure of the sphincter mechanism. In addition, there is a complex neural control which co-ordinates urethral and bladder function to alter from storage to voiding at socially acceptable times.

The causes of incontinence in females:

Restoration of continence in women affected involves a thorough knowledge of normal functioning anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract as only through improved understanding of disease mechanisms can rational treatment be applied.

Figure 2: Incontinence types; Stress, Urge and Overflow

Population studies from numerous countries have reported that the prevalence of UI ranged from approximately 5% to 70%, with most studies reporting a prevalence of any UI in the range of 25–45%. The reported prevalence of UI among women varies widely in different studies due to the use of different definitions, the heterogenicity of different study populations, and population sampling procedures. However, it can be concluded collectively from these studies that prevalence rises with:

Supervised bladder training, pelvic floor exercises, advice on fluid and caffeine intake, and lifestyle advice may all positively impact UI, frequency and OAB.

Pharmacological treatment may also help to improve the symptoms. Antimuscarinics/anticholinergics and the beta-3-agonist mirabegron are some of the available drug treatment options for UI, frequency and OAB. Anticholinergics inhibit binding of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors in the detrusor muscle, thus reducing involuntary detrusor contractions without disturbing normal voiding.

Antimuscarinics (first line drug treatment as per NICE guidelines) ie fesoterodine, oxybutynin, solifenacin, tolterodine, trospium. The preferred drug as per HSE medicine management publication for UI, frequency & OAB is tolterodine ER (extended-release).

Tolterodine ER: the dose for adults including elderly is 4 mg once daily. In hepatic impairment, the dose is reduced to 2 mg once daily. Adverse effects such as dry mouth, constipation, dizziness are quite common with antimuscarinics. Where there is no/inadequate improvement in symptoms after at least 4 weeks of treatment, or where adverse effects are intolerable, switching to an alternative antimuscarinic or mirabegron is considered.

Mirabegron: a selective beta-3-agonist is recommended as an option for treating symptoms of OAB for people with whom antimuscarinic drugs are contraindicated, clinically ineffective or have unacceptable side effects. The usual adult starting dose of mirabegron is 50 mg once daily. A reduced dose of 25mg once daily is advised in

Other drug treatment options include:

Desmopressin: a synthetic analogue of vasopressin and thus acts as an antidiuretic. Desmopressin administration does carry risks such as fluid retention and hyponatraemia. It is advised to limit fluid intake for 1 hour before to 8 hours after taking desmopressin. It is recommended as per NICE guidelines that serum sodium levels should be measured 3 days after the first dose, and if hyponatraemia is suspected, desmopressin should be discontinued. There may be an increased risk of water retention and hyponatraemia if desmopressin is taken concurrently with certain drugs such as; loperamide, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, NSAIDs, SSRIs.

Duloxetine (Yentreve®): is a dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and increases urethral sphincter activation. Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in reducing stress urinary incontinence episodes and increasing quality of life. Nausea is the most common adverse event and the main cause for discontinuation. Other common side effects included constipation, dry mouth and fatigue. For the management of symptoms of stress urinary incontinence the recommended dose of duloxetine is 40 mg twice a day. It is recommended that the patient be reassessed after 2–4 weeks of treatment to evaluate the benefit and tolerability of the treatment. If duloxetine treatment is to be discontinued, dose must be gradually reduced over at least 1 to 2 weeks to reduce the risk of withdrawal reactions.

Topical oestrogen i.e. Vagifem®, Imvaggis®, Ovestin®

In women who have gone through menopause, low oestrogen levels may contribute to urinary incontinence. Topical oestrogens should be used in the lowest effective dose to minimize systemic absorption. The British National Formulary advises that the endometrial safety of long-term or repeated use of topical vaginal oestrogens is uncertain. Consequently, treatment should be interrupted at least annually to re-assess the need for continued treatment. If bleeding or spotting appears at any time during treatment, the reason should be investigated. Investigations may include endometrial biopsy to exclude endometrial malignancy.

References available upon request

Grainne Doyle

Share This Page