The information provided was valid at the time of the publication of this CPD article.

In this month’s CPD article Dr Maria Donovan, lecturer in Clinical Pharmacy Practice at University College Cork, provides an overview of emergency contraception, which includes, among other areas, understanding the menstrual cycle, levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate.

Emergency contraception is indicated to reduce the risk of a pregnancy occurring following unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) or failure of contraception. There are three types of emergency contraception:

The two oral emergency contraceptives, ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel, can be accessed in most community pharmacy settings, following a consultation with the pharmacist. As clinical guidelines are regularly updated, this article summarises the considerations a pharmacist can have when choosing the most appropriate action for a woman seeking emergency contraception.

Emergency contraception is indicated after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI). There is a possibility of pregnancy following UPSI anytime from day 21 after childbirth (unless the woman is fully breastfeeding and amenorrhoeic, in which case pregnancy is possible for months after childbirth). Pregnancy is also possible from five days after a miscarriage, abortion or ectopic pregnancy. Emergency contraception may also be required if regular contraception has become compromised, but it is important to obtain a full history regarding the contraception use and the reason for the woman presenting for emergency contraception to fully understand if emergency contraception is indicated (more later).

Even though a copper-IUD cannot be placed by a pharmacist, it does still merit a mention here. It is the most effective form of emergency contraception, with a reported effectiveness rate of >99.9%. One of the main points to remember about a copper-IUD is that it is the only form of emergency contraception to be effective after ovulation. Therefore, as a community pharmacist, if there is a possibility that the woman has ovulated prior to presenting to the pharmacy, this must be explained to the woman, and she should be signposted to a provider of the copper-IUD. Guidelines from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health (FSRH) which are a UK-based, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) accredited group, state that all women seeking emergency contraception should be advised that a copper-IUD is the most effective method of emergency contraception. The FSRH guidelines suggest that all providers of emergency contraception, should signpost all women looking to access emergency contraception, to a provider of the copper-IUD. However, the guidelines also advise that even if you refer a woman to have a copper-IUD placed, oral emergency contraception should also be provided at the time of signposting, in case the woman changes her mind. It is also worth remembering that according to the Summary of Product Characteristics for each of the oral emergency contraceptives state that they can be taken ‘at any time during the menstrual cycle’.

The two oral emergency contraceptives work by the same mechanism — delaying ovulation. This means two main things: (i) ovulation is still likely to occur in the cycle after emergency contraception has been taken, just at a later date, and (ii) oral emergency contraception does not work after ovulation has occurred. A pharmacist will need to establish that a woman is likely to be in the part of her cycle before ovulation has occurred, by asking questions such as ‘when was your last period?’, ‘is your cycle regular?’ and ‘if your cycle is regular, how many days apart are your periods approximately?’. Once it has been established that the woman is likely to be in the part of her menstrual cycle prior to ovulation, some other questions can help establish whether levonorgestrel or ulipristal acetate will be more suitable.

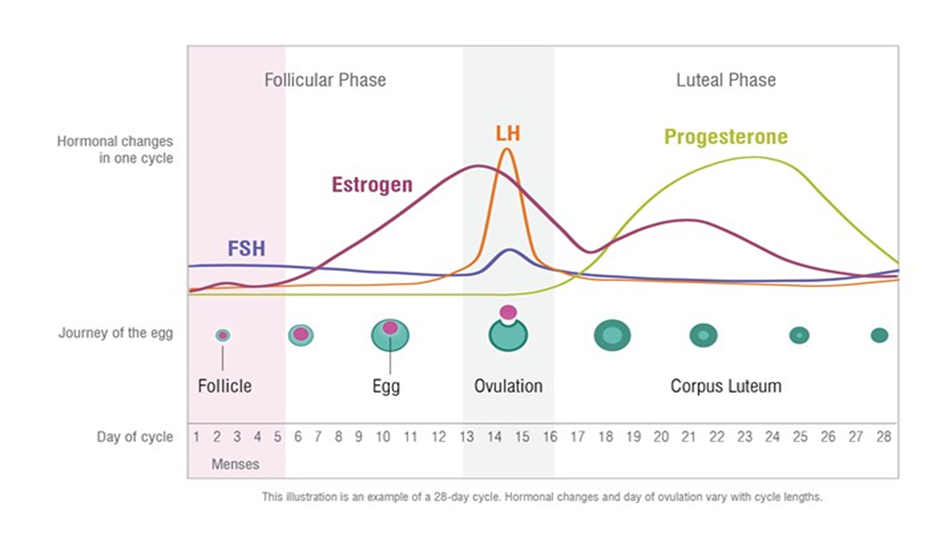

It is imperative that pharmacists providing emergency contraception have an understanding of the hormones and key timings of the menstrual cycle (Fig. 1). Luteinising hormone (LH) provides the trigger for ovulation, and both levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate work by suppressing the luteinising hormone peak, which delays ovulation by approximately five days. In a natural menstrual cycle (no hormonal contraceptives), a pregnancy is most likely to happen if UPSI occurs in the five days before ovulation or on the day of ovulation — this is considered to be the highly fertile time of a woman’s cycle. The reason for this is that sperm are viable in the female genital tract for about five days, whereas the egg is viable for less than one day.

Fig. 1: Natural Menstrual Cycle

With either form of oral emergency contraception, serious side-effects are rare. The side-effects commonly experienced include headache, nausea and dysmenorrhoea. If a patient is so nauseous that they vomit within three hours of taking oral emergency contraception, a further dose of the same oral emergency contraceptive as was given originally, should be dispensed. As both oral emergency contraceptives work by delaying ovulation, both have the side-effect of delaying menstruation. Every patient should be advised to take a pregnancy test if their period is delayed by more than seven days. However, it is useful to know that 20% of patients who took ulipristal acetate have a delay of more than seven days to their period, as do 10% of patients who took levonorgestrel. There are two specific circumstances in which ulipristal acetate is unsuitable due to drug-drug interactions:

Dr Maria Donovan

Share This Page