The information provided was valid at the time of the publication of this CPD article.

Constipation describes the infrequency and difficulty when emptying the bowels. It can affect people of all ages, although it is twice as common in women than men particularly those who are pregnant due to hormonal fluctuations. Approximately 40% of pregnant women experience constipation during their pregnancy. Older people particularly those aged over 70 years are five times more likely than younger adults to have constipation, usually because of several factors, including a more sedentary lifestyle, level of fluid intake, diet and delaying the urge to defecate because of mobility issues. Chronic constipation with faecal incontinence in children is commonly seen by GPs. It affects 4% of preschool children and 2% of school children.

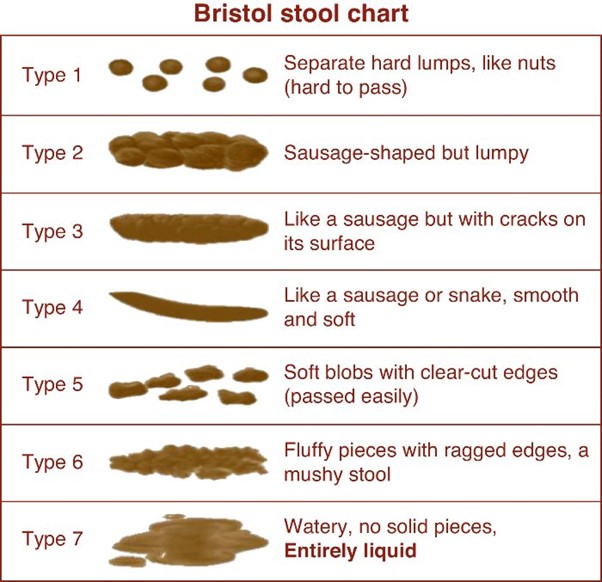

Typical symptoms of constipation include abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, nausea, loss of appetite and straining during bowel movements. In children, as well as infrequent or irregular bowel movements, a child with constipation may also have the following signs and symptoms such as lack of energy, being irritable, foul-smelling wind, soiling clothes and generally feeling unwell. Stools associated with constipation tend to be dry, hard and lumpy and indicated as type 1 or 2 on the Bristol stool chart (Figure 1). The pain and discomfort from chronic constipation and the associated complications can greatly impact a person’s quality of life.

Figure 1: The Bristol stool chart

Chronic constipation can be classified as functional (or idiopathic) or secondary constipation. Functional constipation occurs without an anatomical or physiological cause. A person with functional constipation may be healthy, yet has difficulty defecating leading to believe it maybe neurological, psychological or psychosomatic. It is diagnosed by the exclusion of a pharmacological or medical cause. Secondary constipation is generally caused by a drug or medical condition.

Conditions known to cause constipation include disorders that alter the functionality of the GI tract, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis can also have direct effects on the nerves that control bowel function resulting in uncoordinated contraction of abdominal muscles and inhibiting the passage of stools. Secondary constipation can occur in patients with diabetes and hypothyroidism due to weight gain and reduced mobility associated with such conditions.

1. Antihypertensives (diuretics, clonidine, calcium channel blockers)

If clinically appropriate switch to less constipating medicines such as ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers or angiotensin-II receptor antagonists. Diuretics can cause constipation due to less available fluid. Laxatives such as docusate can act as a surfactant and softener or osmotic laxatives can be used to increase the amount of water in the large bowel.

2. Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline)

Serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors are alternatives less associated with constipation.

3. Antimuscarinics (procyclidine, oxybutynin)

These agents decrease GI motility and therefore a stimulant laxative may be necessary.

4. Antiparkinsonian medicines (levodopa, dopamine agonists, amantadine)

5. Iron supplements

Intravenous iron could be used, or a laxative may be co-prescribed.

6. Aluminium-containing agents (sucralfate and antacids)

Proton pump inhibitors could be used instead.

7. Analgesics (Opioids and NSAIDs)

Opioids cause constipation by decreasing peristalsis and enhancing the resorption of fluids and electrolytes. A stimulant laxative e.g. senna is recommended at the lowest effective dose. Osmotic laxatives are also effective for this type of constipation and are often better tolerated than stimulant laxatives which can cause abdominal cramping.

Pregnancy: Constipation is mostly experienced during the early stages of pregnancy as a result of hormonal changes. During pregnancy more progesterone which acts as a muscle relaxant is produced. As food moves through the gut, the gut wall muscles contract and relax in a rippling wave-like motion. The increased progesterone interferes with the contraction of the bowel muscles making it harder for waste products to move along.

In young children: About one in three parents report constipation at some time in their child’s life. Poor diet, fear about using the toilet and poor toilet training can all be responsible.

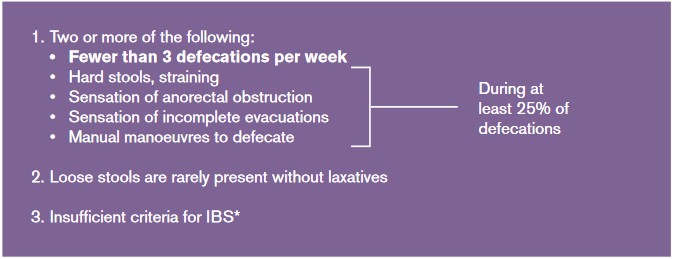

Figure 2: Rome III diagnostic criteria

Lifestyle advice can help to prevent and alleviate constipation. In many cases, constipation may be as a result of poor diet and lack of exercise. Patients should be encouraged to increase fibre in their diet and fluid intake before trying laxatives.

Figure 3: Toilet position

Pharmacological treatment may be required if lifestyle changes do not fully alleviate symptoms of constipation. The NICE guidelines advices that prescribing of laxatives for adults are limited to the short-term treatment of constipation when dietary and lifestyle measures proved unsuccessful or if there is an immediate clinical need.

Faecal compaction occurs when hard dry stools collect in the rectum causing an obstruction. Faecal compaction may initially be treated with a high dose of osmotic laxative macrogol followed by a stimulant laxative days later. If this combination is not successful, a suppository (e.g. bisacodyl or glycerol) or mini enema (e.g. docusate or sodium citrate) may be administered.

“The NICE guidelines advises that prescribing of laxatives for adults are limited to the short- term treatment of constipation when dietary and lifestyle measures proved unsuccessful or if there is an immediate clinical need.”

References available upon request.

Grainne Doyle MPSI

Share This Page